The ongoing impact of the pandemic on our educational systems is certainly unprecedented, with remote learning continuing longer into the 2020-2021 school year than most would have thought possible when COVID struck. Time out of the classroom, away from educators and the structure and support systems they provide to students, has dramatically slowed student learning—so much so that researchers are labeling this phenomenon the “COVID slide.”

Faced with ongoing challenges, many states have requested or are contemplating waivers for Spring 2021 testing, citing concerns about fairness and equity in administration, as well as the validity of scores for accountability data. These concerns are real and justifiable. The pressures on educators, families, and students alike are considerable.

However, as we now face the possibility of a second straight year without state testing, we must consider an important question: how to weigh the technical and operational challenges of testing this spring against the need to initiate a years-long-recovery effort beginning this summer that will most certainly require good data. Insights into how students’ very uneven learning opportunities over the last year have impacted their growth will be more valuable to educators than ever before. Thus the paradox: we need good data to shine a light on how to recover and start to close the equity gap widened by the pandemic, but there is hesitation to test due to equity concerns, which of course is the mechanism that provides the data so critically needed.

In short, to navigate the many obstacles to recovery, we need good data to light the way.

Early Indicators of Unprecedented Impact

Academic recovery will start with getting students back into school as soon as possible. Reports of nearly a third of students from high-poverty schools simply “disappearing” from online learning due to lack of access to computers and broadband connections underscore the moral imperative of returning to in-person learning. While roughly 60 percent of students nationwide are still learning remotely, experts estimate that only 49 percent of White students are learning from home while 70 percent of Black and Latinx students are. COVID’s impact on student learning has without question been uneven and inequitable, unfairly hitting students of color and students from low-income homes the hardest.

These disproportionate impacts that are exacerbating achievement gaps will be long lasting—perhaps for a generation. Results from interim assessments administered in districts around the country this fall provide an early indicator of the magnitude of learning acceleration students will require to get back on track. Most students were four to seven weeks behind expectations in reading and eight to 11 weeks behind in math. In other words, students were a quarter to a third of a year behind in math, and that was as of October. Certainly, things have not improved since then, especially for those students who have disappeared from remote learning programs. For those students, we are looking at catastrophic delays in their progress toward graduating high school ready for college and career. No school system has ever demonstrated accelerating student learning in math by eight to 11 weeks in a single year. We are clearly looking at an unprecedented, multiyear intensive effort to get students back on track.

It is not too soon to start talking seriously about our “Marshall Plan” for academic recovery.

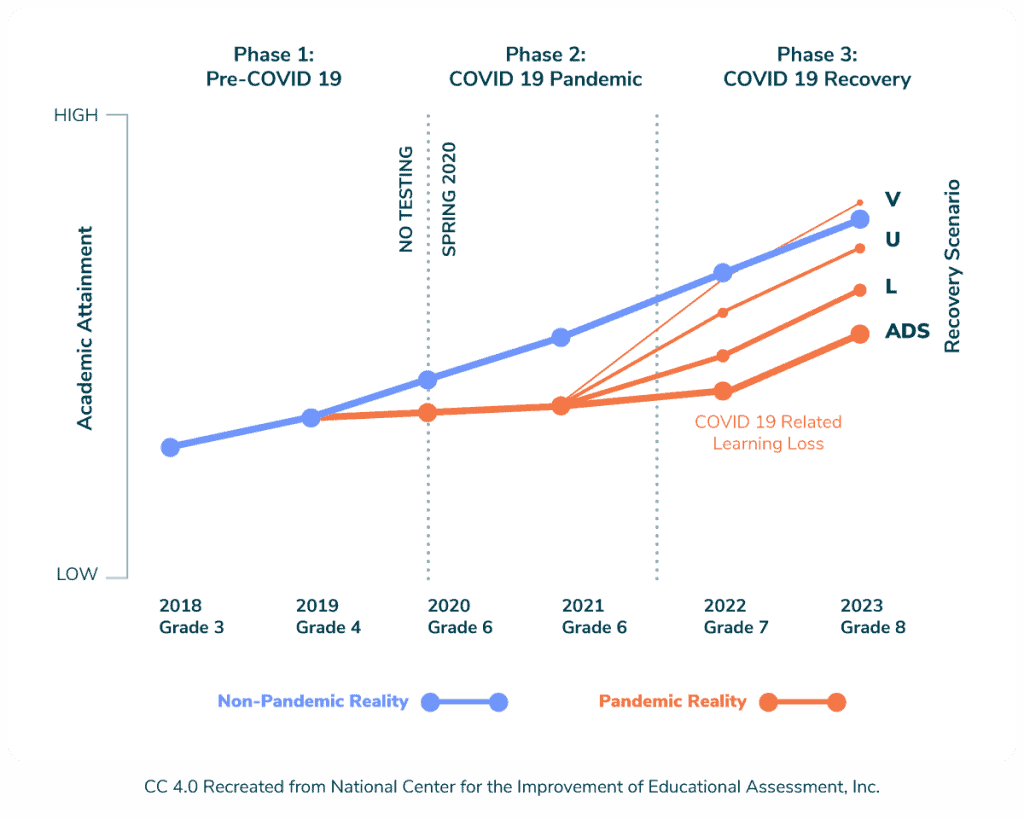

An Equitable Recovery Effort Requires Comparable Data

Such a plan must start with good data. As Damian Betebenner explains in his recent article, recovery—like the pandemic’s effects—will also be uneven and inequitable. Some students (statistically speaking, White and Asian students from higher-income homes who attend higher-performing schools) will likely respond quickly in a “V-shaped” recovery. Other students (statistically speaking, Black, Latinx, Native and English-learner students from lower-income homes who attend lower-performing schools) may very likely not receive the same levels of support and therefore, despite their efforts, remain permanently behind their peers in an “L-shaped” recovery, or even get trapped in an “academic downward spiral.”

Clearly, our recovery plans cannot be a one-size-fits-all commitment to simply return students to school as we knew it pre-COVID. We must target our recovery response by answering three critical questions as quickly as possible:

- Who has been most academically impacted by COVID?

- What grades and subject areas have been most impacted?

- And how much have they been impacted?

As Betebenner points out, we are almost completely in the dark as we try to answer these questions. We don’t know who has been most impacted, in which schools, or how much. While classroom grades can inform instruction, they can’t provide a reliable, unbiased view across schools and student groups. Nor can district-level interim assessments provide a reliable measure. Students of color from low-income schools were disproportionately left out of the fall interim testing, almost certainly underreporting the true impact on their learning. Only a high-quality, statewide assessment directly aligned to the state’s learning standards can come close to ensuring that all students are represented in the data, so that no students fall through the cracks.

Yes, it is a hard year to test, and there are many challenges. But “equal” recovery efforts for a pandemic with unequal impact will only further the inequities of an unequal educational system. We need the best baseline data we can get as soon as possible to begin the years-long work that lies ahead.